Conflicts between farmers and pastoralists in the Sudano-Sahel have been going on for centuries. Over time communities have developed techniques to resolve these conflicts and mitigate their destabilizing effects. These resolution mechanisms were usually informal, and ranged from customary courts, to assess compensation for livestock or crop damage, to dispute mediation by reputable traditional figures or councils of elders. In recent years, these informal tools have struggled to cope with the rapid spread of small arms, the growing power of NSAGs and terrorist networks, and deteriorating social and political stability. Customary leaders and local institutions are seeing their influence diminish or be co-opted by the State or insurgent groups. Relations between the nomadic and sedentary groups who have long lived together in diverse societies have deteriorated. As they travel to other regions, pastoralist groups are treated as “strangers” or “foreign invaders” and subject to exclusion and suspicion. Disputes over livestock have sparked horrific acts of tit-for-tat violence.

In Mali and central Nigeria, farmer-herder is a major element of ongoing tensions between pastoral Fulani and other ethnic groups. In 2018 in Plateau State, Nigeria, ethnic Fulani and Berom herders blamed one another for a series of unresolved cattle thefts, which eventually escalated into a two day massacre of civilians in Barkin Ladi in which more than 200 people lost their lives. The attacks inspired a reprisal where Berom youth attacked Fulani travelers on a highway. A similar massacre occurred in the Malian town of Ogossagou, when members of an ethnic vigilante group killed 160 people in a town largely populated by a rival herder community, which sparked further reprisals.

Such exclusion has become more severe in recent years with the rise of violent extremism and ethno-nationalist militias. In CAR, for example, self-defense militias formed with the stated goals of defending against armed bandits who included Arab and Mbororo pastoralists, even as state security forces clashed with NSAGs who claimed to be defending pastoralists. As fear and suspicion intensified following the uprising by the rebel Seleka coalition in 2013, “anti-balaka” militias began attacking all Muslim communities, including Mbororo pastoralists who were presumed guilty by association. These attacks led to a spike in mobilization by Mbororo communities to retaliate and defend themselves, as well as new iterations of NSAGs led by Mbororo such as the Unité pour la paix en Centrafrique and 3R.

Many pastoralist and farming communities prefer to resolve disputes by allowing trusted elders or chiefs to mediate, particularly as they are often unable to depend on state justice institutions that are absent or unfamiliar. Traditional mediation practices have been an important tool for resolving complaints over crop damage, livestock theft, or assault before they escalate into something worse. However, many of the traditional dispute resolution practices in the Sudano-Sahel have been corroded by years of instability, political and social polarization, and armed violence. Without credible channels for parties in a dispute to agree upon a resolution, pastoralists and farmers increasingly turn to militias or mob violence to get justice. Increasing the capacity of the formal justice sector in these regions is a critical step (see Strategy – Access to Justice), but it is also important to support options for alternative dispute resolution (ADR). Dispute resolution practices that rely on trusted community leaders will be familiar to many pastoralist and farmer communities and are necessary for finding flexible solutions to the kinds of problems they encounter. When a group of farmers begin cultivating land in the middle of a well-established transhumance route in public land, there may be few legal solutions available to pastoralists, but they may be able to negotiate a solution if there are trust mediators who can intervene. External interventions may involve, for example, providing technical training to local leaders or helping to set up a local peace committee.

Though pastoralists and farmers have cohabitated in eastern DRC for generations, political tensions and the proliferation of armed groups in recent decades have eroded the traditional mechanisms by which these communities resolve disputes. Clashes between armed groups and military forces have displaced many pastoralists, who are forced to take their animals to new areas where they do not have established agreements with farming communities and inevitably the animals stray onto farmland. Many of the herders – who often do not own the livestock themselves – are stretched thin. Despite laws requiring that there should be one herder for every eight cows, some are managing a hundred or more.

In the absence of effective mediation options, these disputes have incited cycles of retaliatory violence – farmers killing trespassing livestock or pastoralists taking up arms to protect their herds. In response, Search – along with the International Rescue Committee (IRC) and South East Asia (ZOA) – established a series of local peace committees in 18 villages in coordination with local leaders and village chiefs. Committee leaders were trained on contemporary mediation techniques and have used their expertise to settle upwards of a hundred disputes within a year period. This has allowed local communities to have a viable alternative to either violence or reliance on higher authorities that are often inaccessible.

Conflicts between pastoralist and farming communities are often deeply interwoven with group identity and interethnic tensions among different pastoral groups or between pastoralist and sedentary groups. Many established practices for building intergroup trust are grounded in Contact Theory – the hypothesis that regular contact between two groups can increase tolerance and acceptance. However, building intergroup acceptance through programs that rely on regular people-to-people contact can be challenging given that the nomadic livelihood of pastoralists involves social and political distance from local residents. Yet pastoralists are never completely isolated from settled communities – many live in their own settlements when they are not on migration with the livestock, or maintain regular contact with the people they meet along their migration routes or when they travel to markets. There may be a number of opportunities to bring pastoralists in contact with their settled counterparts through common interests such as markets or cultural events. Leveraging these common interests, people-to-people interventions can uproot the fears and skepticism between pastoralist and sedentary communities or among conflicting pastoralist groups.

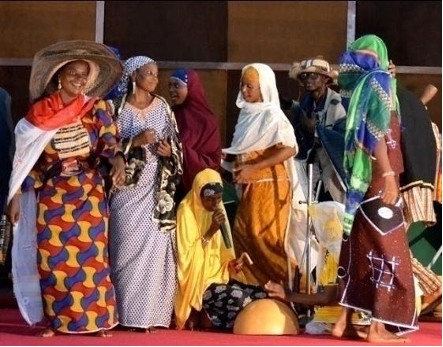

In response to rising hostilities between Fulani pastoralists and sedentary farmers in Nigeria’s Middle Belt in 2016, Search for Common Ground hosted a series of public performances of a dance production called “I Follow the Green Grass.” The performance presented Fulani pastoralist lifestyles rarely seen by outsiders. Part of this portrayal involved community conflicts and how these were overcome. A film version was later screened as part of a mobile cinema project. These screenings allowed citizens from diverse ethnic backgrounds to share their reactions and concerns about the state of intercommunal hostilities.

Photo: Boy participates in a discussion during a screening of “I Follow the Green Grass” in Jos, Nigeria. Credit: Search for Common Ground

The pastoralist way of life is more than a means of survival; it is both the source of group identity and a unique cultural heritage. This cultural pride is a defining asset and an opportunity to educate others who inhabit the same lands but fear pastoralists. Events designed to highlight the diversity of cultural heritage among all those inhabiting these unique landscapes can reinforce solidarity and help prevent the escalation of future conflicts. Such events can also remind state officials and the wider public that pastoralism is more than an ancient means of survival, but a celebration of human adaptation and perseverance in a harsh, demanding climate.

Traditional wrestling is a popular sport in South Sudan that has served as a cultural connector between communities that have been divided by civil war, including pastoralist groups like the Mundari or Dinka. Tournaments in Juba and other urban centers bring together groups from across various tribes and ethnic groups to compete over prizes like cattle. The events can attract large public crowds and help to restore good faith between communities that may be parties to conflict or cattle raiding.

Transforming relationships between mobile and sedentary communities can be complicated by physical distance across remote landscapes with little communications technology, digital or otherwise. The absence of face-to-face encounters in a region dominated by violence can intensify this polarization. Where people-to-people programming is unrealistic because of conflict or physical distance, mass media (radio, television) and direct communication tools (phone services, social media) can help bridge groups across dividing lines, rebuilding trust and solidarity. Telecommunications services may be limited or inaccessible to communities living in remote areas, but there are still a variety of ways in which communications tools can be used creatively to reach mobile populations.

In eastern Central African Republic, conflicts have arisen between mobile Peuhl and local farmers. In response, Invisible Children enlisted all parties, including local authorities, in messaging campaigns to counter these hostilities. Messages and music were recorded in Fulfulde (the language spoken by Peuhl pastoralists across Central Africa), with civil society leaders even traveling to a Peuhl wedding to record traditional music. The messages and music were then loaded locally onto micro SD cards to be disseminated among pastoralists, copying a popular way for pastoralists in that region to share music or other media.

Photo: An SD card used by Invisible Children in phone. Credit: Nathan Garcia for Invisible Children, 2018

Public messaging around pastoralism and conflict risks stoking hostilities through implied blame or accusation, fueling deeper identity-based tensions. Media personalities, diplomats, and other public figures play a critical role in shaping whether people see pastoralists as violent invaders or members of a common community (see also Module – Law Enforcement & Counterterrorism).

Various insurgent movements in the Sudano-Sahel have built support by appealing to pastoralist grievances or ethno-religious identities, from the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara to the UPC in the CAR. A principal part of the platform of the Katiba Maacina insurgency in Mali, for example, is free access to the rich grazing resources of the inland Niger Delta and these appeals have resonated among Fulani pastoralists who make up a significant portion of the group’s membership. The participation of (traditionally pastoralist) Fulani communities in organized insurgencies and intercommunal violence is often portrayed in the media and public discourse as a move toward “Fulanization” or “Islamicization,” rather than a response to competition over resources. Even when this rhetoric is employed to draw attention to violence committed against civilians – as in the case of violence against Dogons in Mali or Christian farmers in Nigeria – it can have damaging consequences. The use of such charged language can erode the important distinction between the Fulani as an ethnic people numbering in the tens of millions and the small number of people who engage in insurgent or violent activities.

Photo: Fulani men in Mali. Credit: Leif Brottem